60 – My blogs – and a summary rant

I have now reached ‘Listening Cherry’ number sixty, and this seems like a good moment to look back at the previous Cherries, and the thirty-nine non-Cherry blog posts that preceded them. And I’ll end with a summary rant, or a ranted summary of my current idée fixes.

Just below is a set of four lists of the ninety-nine blog posts that I have written since 2011. Each list gives month and year of publication, the title of the blog, and in the fourth column a characterisation of the nature of each blog. These range from ‘funny-ha-ha’ through ‘info’ ‘review’ ‘yippee’ and ‘discussion’ to ‘rant’.

The 2011-2012 index is here

The 2013-2015 index is here

The 2016-2017 index is here

The 2018-2020 index is here

The Blog categories

I have assigned the following category-labels to the blogs:

- funny-ha-ha means that (at the time I wrote the blog) I thought the blog was very funny

- info means that the blog contains information about what I was doing at the time

- review means that the blog is reviewing/mentioning the existence of someone else’s publication

- yippee means that I was congratulating either myself (usually) or someone else on a professional achievement

- discussion means that the blogs were part of a discussion after an online presentation

- rant means that the blog attacks some of the idiotic foolishnesses in beliefs or practice of the ELT profession

- poetry means that the blog concerns recordings of poems (Shakespeare and Larkin)

If you want a quick introduction to my way of thinking, read this post about my key metaphor (Greenhouse, Garden, Jungle) which has been found very useful by both teachers and learners. To follow through, go to the blog menu and search for rant. Final rant follows, containing some key ideas.

Celce-Murcia et al – a foundational statement

I always quote Celce-Murcia et al. in their Teaching Pronunciation 2nd Edition

… our goal as teachers of listening is to help our learners understand fast messy authentic speech … The spoken language our learners need to comprehend is much more varied and unpredictable than what they need to produce in order to be intelligible … The goals for mastery are different

Celce-Murcia, M. Brinton, D.M. and Goodwin, J.M. (with Barry Griner) Teaching Pronunciation 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press

Celce-Murcia’s book is about Teaching Pronunciation (it’s no secret, it’s the title). As such, despite the quotation above, it stays firmly in Greenhouse and Garden. And quite reasonably so. But we need more books, activities, and courses to help teachers and students embrace the messiness of the Jungle. Because ‘the goals for mastery are different’, we need a different syllabus, and different activities for listening. Entirely different from what we currently teach about Greenhouse and Garden styles of speech. This is what my books, Phonology for Listening and A Syllabus for Listening – Decoding are about.

Ban ‘pronunciation’

I would ban the use of the word pronunciation in teaching listening, and use the word soundshape instead. All listening classes should include instruction on the numerous soundshapes words can have. All words have multiple soundshapes, not just the function words and the so-called ‘weak forms’. ALL WORDS HAVE WEAK FORMS. The questions to address in listening activities is NOT ‘how is this word pronounced here?’ or ‘How should this word be pronounced?’ but ‘How many soundshapes can this word have?’ and ‘How can I prepare myself to hear and understand in the future?’

Expert speakers are deaf to the true nature of the sound substance of speech

Everyone should heed Gimson’s warning

… it is wiser to listen to the way in which a native speaker speaks rather than to ask his opinion.

Cruttenden, A. (ed.) Gimson’s Pronunciation of English 8th edition 2014, Routledge p. 333

Native and expert speakers of English ARE DEAF to what is going on in the sound substance of speech. They suffer from ‘the blur gap’ about which you can read more here and here. In addition, everyone should pay attention to Helen Fraser’s work in forensic phonetics and its implications for teaching listening. You are deaf because you are primed by your expertise in language to believe that speech is much clearer (more Greenhouse and Garden-like) than it actually is. Additionally, you can be primed to hear virtually anything if you are told in advance what to hear. If someone tells you that a song lyric contains the words ‘staple the vicar’ then that is what you will hear, and it will make it very difficult for you to hear the original words. Demonstration here (contains some rude words, but you will laugh your socks off).

Beware the smiling class imperative

In A Syllabus for Listening – Decoding (p. 48) I mention ‘the smiling class imperative’ which is an obstacle to the effective teaching and learning of listening. This imperative is the urge to have your class smiling, and/or interacting happily giving you a ‘I’m a good teacher’ buzz. Its existence means that you are disinclined to take them into the Jungle and help them with the (non-smile-inducing) puzzling mess and the (frown-creating) disorienting unruliness. You’ve got to spend time with, and help students with the non-smiley frowny stuff, you’ve got to be comfortable in a bad-mood class.

Gap-fill

You may believe that doing loads of gap-fill exercises is the way forward. They help, but there are dangers to gap-fill exercises as you can read here, here and here.

English as a Lingua Franca

One of the big developments in ELT during my career is the English as A Lingua Franca (ELF) movement. I think the movement is wonderfully liberating as far as pronunciation models are concerned, but – for me – issues around coping with the Jungle remain the same. I have written blog-posts on ELF here, and here.

Don’t believe a word

Lastly. Don’t accept what people or textbooks tell you about speech, however revered, famous or best-selling they might be. Evaluate what they assert against your experience of language. Record natural language and cut it up with an audio editor such as Audacity or (my favourite) Amadeus Pro. Educate yourself, test out other people’s assertions.

Goodbye for now

I’ve enjoyed doing these blogs over the years. But this is my last, as I go on to the next phase of my life.

59 – Microwave ready meals

The way we teach listening is not effective.

We have recipes and ingredients. But what we do in listening activities is akin to being at a cookery school where pupils are eager to learn how to cook exciting things.

But they are disappointed to find that the course consists only of smelling and tasting pre-cooked oven-ready or microwave meals.

They are dismayed that they cannot cook for themselves, and blame themselves for being poor students.

In class they are asked to guess what the ingredients are, who might eat this meal, at what time of day, and what those who eat it might think of it.

Nothing on the choice and shaping of ingredients, and how they interrelate. No teaching about the key components and how they might occur again in other dishes.

Yuk.

Image from here.

58 – Teaching well is a problem

We teach listening well – that’s the problem. We have a well-established listening comprehension methodology which counts as/masquerades as ‘all we need to do to help learners achieve their listening objectives’.

It has evolved over decades to fit what we think our learners can (sort of) manage and what teachers can actually manage. To qualify as a teacher, and to be thought a good teacher requires mastery of this methodology. But what if the methodology is off-target? (And actually it is). What if it has evolved to stay within or close to the comfort zone of the other things we do (reading, sentence grammar, pronunciation)? And what if mastery of natural speech requires frequent excursions outside the comfort zone and acceptant of the unruly nature of speech?

But we are hamstrung by our devotion to rules-and-exceptions and in particular to our adherence to the dictates of (a) the fairy-tale beautiful princess of correct pronunciation and (b) the handsome prince of connected speech rules.

The sound-substance that our students encounter outside the classroom (aka natural speech) bears no resemblance to the prince and princess of a fairy story. To the extent that we adhere to the fairy-tale fictions, we imprison our learners within the walls of the castle of a fantasy world.

Natural speech is not generated from a list of rules-and-exceptions. Nor does it issue from the mouths of castle-bound princes and princesses. It emanates from the Jungle where any ‘rule’ we may expect to find there will be swamped/swarmed/stamped/bitten/chewed into an infinity of tiny exception-like pieces.

For the learning of listening to be more effective, we need to teach less well – forget our fictions, let down the castle drawbridge and let the Jungle take over the castle – let our students encounter reality, and help them master it.

57 – ‘Soundbites’

I used to think that Jungle features occurred only in recordings of spontaneous, unscripted speech. But I now realise that features of the Jungle can occur in scripted recordings for which are part of textbooks. I recently came across an example in a recording from Dellar and Walkley’s Outcomes Advanced. In unit 8 (Track 24 of the split edition) there’s a dialogue between two people talking about a holiday in the Dolomites. At one point the female speaker reassures her male listener that what he thinks is a dangerous situation (in climbing a mountain) is actually quite safe. The conversation goes

A: Really? I’m not sure I’d trust some rusty old cables

B: No, they’re fairly secure. I mean, you need a head for heights, but it’s fine.

Have a listen.

And here are the last three words ‘But it’s fine’

When I first gave this soundfile a careful listen, I thought there was something interesting happening in terms of the sound shapes of ‘but it’s fine’ so I isolated them, and made this sound file.

To my ears (it is so important to say that!) but it’s sounds close to a monosyllable bites |baɪts| or even bite |baɪt|. Depending on the quality of your audio system, and the quality of your ears you may not hear a final |s|. So what is happening? And how do we describe it? Well, here goes – first the vowel quality:

Why is the strut vowel not present, why is the vowel quality close to a trap vowel? Probably because of an accent difference – as my colleague Mark Hancock helpfully suggested – ‘the strut vowel is very open in the South of England’ close to bat |bat|. Given this vowel quality, how can we explain the rest of what is going on?

- the word but, now |bat|, experiences a t-drop |bat| and becomes |ba| and …

- the exposed vowel teams up with the vowel of it’s to form a vowel with glide sounding like the diphthong |aɪ| resulting in a syllablend bites |baɪts|

- (terms from Cauldwell, 2018)

Going back to my starting point – even in the scripted recordings of textbooks, we can expect to find Jungle features which are not adequately described by our conventional ‘rules of connected speech’. And not just in Advanced textbooks – in the Outcomes series, all levels (including Beginner) feature recordings of both slow and fast versions of sentences – which have a delightful variety of Jungle features.

56 – Reasonable hearings

I was recently invited to give a two-day workshop in Moscow on Listening-Decoding. For me, this kind of opportunity is a gift from heaven. And although I found the experience somewhat knackering, my hosts looked after me very well and I experienced the workshop as both an uplifting and energising event.

One of the things I did at the event was to exploit the recordings of Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley’s series Outcomes. This series of course books (Beginner all the way through to Advanced) features recordings – even at the Beginner level – which give both fast and slow versions of the same sentence.

I used one sound file early on in the workshop which comes from the Grammar Reference part of the Beginner Book, and for which the instruction is to ‘Listen and complete the questions – they are fast’. The students see a gapped sentence and asked to complete it – in this case the gapped sentence they saw was the question

‘How much xxx xxxx?’

And here is the sound file:

So of course, the words ‘are they’ should be written in the gap. But I was curious to find out what the sound shapes of ‘are they’ were so I isolated them and cut them out into this sound file:

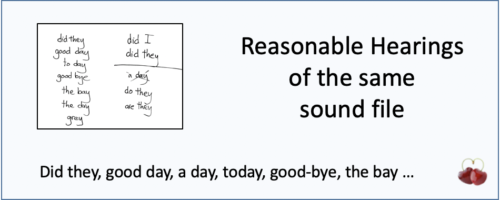

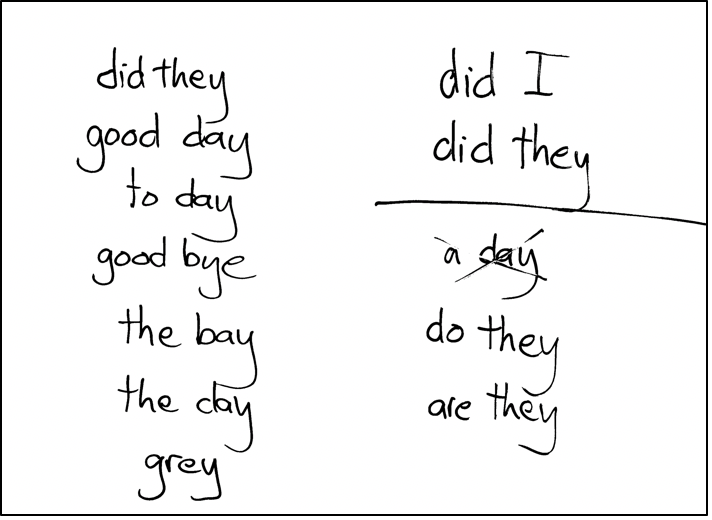

On hearing this, I thought it sounded close to ‘a day’. So I thought it would be worth experimenting – in the workshop – with this sound file, and ask the participants what words they thought the soundshapes represented. So I played the short file first, and elicited from them – to the whiteboard – what they made of this short sound file. Below is a photograph of the whiteboard.

(I can’t remember why I crossed out a day)

Isn’t that range of hearings wonderful? These are all what I term ‘reasonable hearings’ or ‘alternative hearings’ of the sound substance of this short extract. They represent honest assessments (guesses) as to what the intended words were. So I used this moment to make the ‘hearings’ point that is in my A Syllabus for Listening – Decoding p. 18 and throughout. What I should have done (hindsight moment now) was to get the room to do vocal gymnastics with all of their suggestions. So using the frame ‘How much xxx xxxx’ they substitute all of their suggestions in turn in the gap – starting slow and speeding up but making a mush of the last two syllables:

How much are they; How much did they; How much good day; How much today; How much the bay.

Something like this, which goes from Garden to Jungle:

The purpose being, of course, to get familiar and comfortable with the mess and unruliness of the Jungle of natural spontaneous speech, to become better listeners.

55 – Treasuring word clusters

In my work I focus on word clusters as a key element of speech to focus on in the teaching of listening/decoding. The term ‘word cluster’ comes from Carter and McCarthy’s ‘Cambridge Grammar of English’ (2006), examples of word clusters include ‘a bit of a’ and ‘I was going to’. Other authors refer to them as recurrent chunks or formulaic chunks (Field, 2008: 155). Such clusters are an important component of all types of language, and I argue in ‘A Syllabus for Listening – Decoding’ that they are an essential component of the listening syllabus for all levels of learners, even advanced. It may seem surprising that I mention advanced learners but I do so because John Field’s research has shown that even advanced learners have difficulty with such clusters (Field, 2008: 146).

Another reason for focussing on them is that they occur across a wide variety of speech styles and topics. So learning the variety of possible sound shapes of these clusters provides high surrender value. But why do so, you may ask, surely we can ignore these bits and simply focus on the content words and thereby build meanings. No, no and three times no! Not if our learners want to learn the language, and not simply indulge in communicative coping.

Recordings as treasure troves of meaning

All recordings are treasure troves of sound shapes and soundscapes of the words and speech unit. All of the recording – not just the set of content words it contains – provides matter for teaching and learning. To go metaphorical for a moment – the gems of meaning are contained in, and surrounded by, layers of mineral substance – the sound substance of clusters of very common words. The way we currently focus on the meaning gems alone in our listening classes results in testing and coping activities, which don’t allow room to learn about, and learn how to handle, the mineral layers of sound substance in which the gems occur.

Clusters are fast

Part of the reason why word clusters are challenging for advanced learners is that they are often much faster than their immediate neighbours in the stream of speech.

Take for example one of the closing sentences of a TED talk by Julian Treasure, which goes

I’m going to leave you with with a little bit more birdsong

TED 660 JULIAN Treasure The 4 ways sound affects us 21 July 2009

Interestingly, the TED transcript gives fewer words than this: I’ll leave you with more birdsong – omitting words which don’t contribute hugely to meaning is quite common in such transcripts. The length of this talk is 5 minutes 26 seconds, with an average speed of 207.42 words per minute (as measured by the TED Corpus Search Engine here).

Speed of the sentence

I measure the duration of this sentence at 1.7 seconds. If we take a Garden approach to counting words (counting standard contractions – I’m and gonna – as single words, and I’m gonna as three syllables) then

- there are 10 words

- the speed is 5.9 words per second,

- which comes to 354 words per minute – 75% faster than the average speed

- there are 13 syllables

- the speed is 7.7 syllables per second

- which comes to 460 syllables per minute

So this whole sentence itself is already much faster than the talk as a whole. At this point I would like to compare the speed-in-syllables of this sentence with the speed-in-syllables of the recording as a whole, but I don’t have this available to me, but see below for more on speed as measured in syllables.

Speed of the cluster

Let’s turn our attention to the five-word cluster with a little bit more.

- I measure the duration at 0.663 seconds,

- there are 5 words

- the speed is 7.5 words per second

- which comes to 450 words per minute –

- there are six syllables

- the speed 9 syllables per second

- which comes to 540 syllables per minute

Thus this sentence goes at more than twice the average speed of the talk as a whole (207.42) and ca. 30% faster than the full sentence in which it occurs. Let’s now turn to a syllable count:

Just as I mentioned above, at this point I would like to compare the speed in syllables of this cluster with the speed-in-syllables of the recording as a whole, but I don’t have this available to me. However what we can do is compare it to the notions of ‘fastest’ speech in the research literature. A commonly accepted measure in the research literature of the ‘fastest’ speed for spontaneous speech is at 324 wpm or 5.4 sps (Field, 2019:63; Laver, 1994:541). This is way lower than both the sentence and the word cluster that we have looked at.

Does anyone know of any research into speed of speech that looks not just at minute-measured averages, but (as we have done above) what the extremes are that are hidden by average measures?

54 – Treasuring speed

In my work I jump for joy when I find examples of fast speech, because these are locations in recordings that are likely to prove difficult for learners to decode: soundshapes of words are very likely to have been streamlined – and, if so, are likely to have become unfamiliar and/or difficult to catch. An example of such fast speech I have recently come across is provided by Julian Treasure in a TED talk he gave in July 2009.

One of his closing sentences went: I’m going to leave you with with a little bit more birdsong. But interestingly, the TED transcript gives fewer words than this: I’ll leave you with more birdsong. (Omitting words/fillers which don’t contribute hugely to meaning is quite common in such transcripts.)

TED 660 JULIAN Treasure The 4 ways sound affects us 21 July 2009

The length of this talk is 5 minutes 26 seconds, with an average speed of 207.42 words per minute (as measured by the TED Corpus Search Engine here).

Speed of the sentence

I measure the duration of Julian’s I’m going to leave you with with a little bit more birdsong at 1.7 seconds. If we take a Garden approach to counting words (counting standard contractions – I’m and gonna – as single words, and I’m gonna as three syllables) then

- there are 10 words

- the speed is 5.9 words per second,

- which comes to 354 words per minute – 75% faster than the average speed of 207

- there are 13 syllables

- the speed is 7.7 syllables per second

- which comes to 460 syllables per minute

So this whole sentence itself is much faster than the talk as a whole. At this point I would like to compare the speed-in-syllables of this sentence with the speed-in-syllables of the recording as a whole, but I don’t have this available to me. However what we can do is compare it to the notions of ‘fastest’ speech in the research literature. A commonly accepted measure in the research literature of the ‘fastest’ speed for spontaneous speech is 5.4 sps (Field, 2019:63; Laver, 1994:541). This is 30% lower than Julian Treasure’s sentence.

But if we focus on the verb group (I’m gonna leave you) and the word cluster (with a little bit more) we find that these go at 9.0 syllables per second – whereas ‘bird song’ goes at 4.3 syllables per second. So the average speeds, usually minute-averages (words or syllables per 60 seconds), can hide a wide variation in speeds around the average – from off-the-scale fast (9.0+), to slow and stately.

For me, it is on these very short stretches of speech that decoding work needs to focus. Precisely because they present such a speedy challenge to learners.

53 – The accommodation question

My talks and workshops always involve explanations and demonstrations of fast spontaneous speech, and the consequent variability of sound shapes that occur in this stream of speech. I always emphasise the fact that I am talking about the teaching and learning of listening, not pronunciation, and that the goals for mastery of the two skills are different.

A question, or a point that is often put to me in my talks and workshops is this: Surely people accommodate to each other, so that when people speak they adjust the speed and clarity of their speech according to the ability levels of the person, or people, who are listening to them. And (the question continues) as most of the interactions in English in the world are between ELF speakers, who have learned English as a second language, they will be better at accommodating than L1 English speakers. The underlying thinking that these questions represent seems to me to be ‘Surely we need not bother with this messy stuff that you are presenting – we can rely on accommodation and what we currently do in listening to smooth the way’.

Hey ho!

This brings up loads of things.

[1] This accommodation view adopts (in my view) an over-optimistic view of (a) the range of circumstances in which language interactions take place and (b) the niceness of speakers of English – they are not always willing to be of helpful, or able to be helpful (c) the fact that language interactions often take place under pressure when people don’t have time, or the will, to be nice.

[2] I concede that often interactions can take place where accommodation is possible – speakers facing each other, with at least one of them having the skill to moderate their speed and accent to match the abilities of the person listening to them. But equally often language use either (a) occurs in non-reciprocal circumstance (radio, television, public announcements) where speakers do not know who their listeners are, and cannot adjust to their levels of understanding or (b) in pressure situations, or unfamiliar situations, where urgency required of the task precludes the time required to accommodate.

[3] Perhaps sympathetic accommodation occurs more often between L2 speakers of English, but my experience (though limited) of witnessing such interactions, or at least of analysing recordings of people using ELF, is that the same fast speeds and streamlining effects, and consequent multiple sound shapes often occur. In short, ELF speech can also be messy!

I would like to believe in a world where all interactions in English involve cooperative speakers and hearers who accommodate to each others abilities and needs, and who therefore speak with the clarity and intelligibility that is modelled in textbooks and in the classroom. But I know I don’t live in such a world, and I believe that pretending that we do shortchanges our learners. It gives us yet another excuse to ignore the realities of the speech signal.

52 – Answering questions 2 – That’s horrible!

Sometimes people don’t ask questions – they just exclaim. At a conference in Barcelona, I had just played one of my favourite sound files, one that I call ‘able-zoo’ which consists of a variety of voices, and a variety of versions of ‘be able to’. There was an immediate reaction from someone close to the stage: ‘That’s horrible’. Listen to it below – see if you agree.

This was one of a number of occasions when, on reflection, I was not happy with the response I gave. This response was to the effect that ‘What you call ‘horrible’ is normal for the Jungle’. My answer rode on the assumption that hearing the same words said in different circumstances, by different speakers, would be an enlightening – even delightful – experience which would hammer home the fact that sound shapes of all words and phrases can vary so much.

But actually, presenting examples of sound shapes in such a way is quite counter to our normal experience of speech. (Even though they may be samples of normality). Our normal experience of listening is that we have time to acclimatise to the accents, speech patterns, and individual characteristics of each speaker, and we work with streams of speech which are intended to make sense. Our hearing/listening mechanisms are therefore not accustomed to encounter a sequence of non-sense-making language samples containing ‘the same words’. So when thus confronted with isolated samples of sound shapes joined together in a bewildering chain of ‘same words/different sounds’ the reaction ‘That’s horrible’ seems quite reasonable.

So my short answer (short because I was anxious to progress through my workshop) ignored this dimension of the ‘That’s horrible!’ reaction.

I leap I dance I jump for joy, when I have compiled such chains of sound shapes, forgetting that for people listening to such chains for the first time this can be a shocking challenge. A good starting point for a workshop perhaps.

51 – Answering questions

Years ago, I was very timorous about the questions people would ask at the end of a talk, as I felt they would find a weak link or even a severe fault in my presentation. And their finding it would leave me gasping in panic, red-faced with embarrassment, my credibility shot to pieces, my cover blown.

But the older I get the more confident I get that I’ve got a good, helpful reply somewhere in my locker. I (now) love it when people ask questions. The questions-from-the-audience part of any talk or workshop is something that I now really enjoy (most of the time).

That doesn’t mean that I am happy with every answer I give – the ones that went wrong I still remember with acute embarrassment. But I love it most when someone asks a question from a point of view that I have not thought of, and I find that the questioner has knocked on a door that I didn’t know existed, but behind which a previously un-thought-of proposition emerges in reasonably good order to serve as an answer.

One such question came from a participant at a workshop I gave at the University of Birmingham last year. The question was ‘Which type of Jungle speech do you most dislike?’ (to understand this question, you need to know about the botanic metaphor of the Greenhouse, the Garden and the Jungle – see here).

It has never occurred to me to dislike any aspect of the Jungle (fast messy normal everyday spontaneous speech) the messier it gets, the happier I get: I am reassured that there is something to describe and make teachable/learnable.

So how did I answer this one? Well I said that there is nothing about the Jungle that I dislike, but that if I have a dislike of anything, it is that ELT treats the norms of the Garden (careful, rule-governed, sentence-twinned intelligible speech) as if they are the complete picture of what is true of all speech. In the garden, connected speech rules hold sway. And in ELT, we have had only the rules of connected speech as our metalanguage to help us cope with naturally occuring speech.

Don’t get me wrong, these rules are a helpful first step in explaining what happens when word meets word in phrases and sentences in the genteel circumstances of written text read aloud. But the set of such rules that we operate with in ELT are too much oriented towards the tidy rule-governed styles of speech: they cannot cope with the messiness of everyday spontaneous speech. We need to relish, describe, and teach the mess so that our students can become familiar and comfortable with such speech, so that the task of listening and understanding fast normal everyday speech is made much easier than it currently is.

The next post will concern a reply with which I am not so happy.

More on relishing the messy here.