Listening Cherry 05 – Speech perception – phoneme input

I don’t read sufficiently regularly the research into psycholinguistics of listening. Part of me feels that I should read it constantly, particularly the research into speech perception, as it is the research field which is the closest to my concerns in English Language Teaching. However, I do jump in and read around occasionally, and when I do, I am reminded each time about the number of emotions that I felt on previous ventures into this literature: disappointment (at myself), awe, wonder, and unease .

The first is one of disappointment at my own ignorance – I wish I could understand better what I read, particularly as I feel there ought to be something of real importance for ELT in this field.

The second emotion I feel is awe at the ingenuity of experimental design, ‘Wow, you thought of doing that!’, and awe (again) at their rigour of their research methods – ‘Wow, you have these techniques, and this equipment!’. The third emotion I feel is that of wonder at the findings – typically ‘Wow, you make these small changes and you get these amazing results!’

The unease I feel is that it seems to me lot of the research is not addressing sufficiently the nature of spontaneous speech. Maybe I am just reading the wrong sort of stuff. At the risk of making a complete idiot of myself, here are some thoughts about what I have read recently.

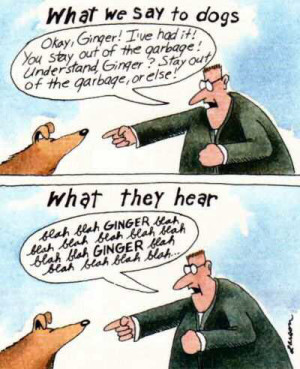

Crudely put, ELT places a tremendous amount of emphasis on top-down effects and strategies (‘native speakers don’t listen for every word, so you don’t have to’) whereas speech perception research places a tremendous amount of emphasis on the detail of how words-in-the-stream-of-speech are recognised. We in ELT have typically avoided getting to grips with the messiness of the sound substance that our students have to cope with if they are to become competent listeners. Instead we focus on the top-down stuff (because it is easy to do). We do loads of schema activation (‘think about your favourite pair of shoes’) and contextualisation (‘listen to this lazy person and this active person speaking about what they like to wear when walking’) and prediction (‘what do you think each one might say about the importance of good footwear’) and we get the students to use contextual knowledge to bridge over the decoding gaps to arrive at the right answers.

Speech perception research on the other hand has a history of a strong focus the the details of the mechanisms by which we recognise individual words in the stream of speech. Some of the models of speech perception belong to a paradigm which can be characterised as the ‘activated-candidates-in-competition’ paradigm which operates using what Magnuson et al 2013: 21 refer to it as ‘the phonemic input assumption’.

The phonemic input assumption ‘works’ by matching phonetic events in the acoustic substance (stream of speech), to phonemes, to words in the listeners mental lexicon.

So, for example, let’s say that a phonetic event occurs (low back vowel), then the phoneme |ɑː| is identified, and the following five words are then activated at that precise moment: are/art/artist/artistic/artistically. They are activated because they all begin with the identified phoneme |ɑː|, and these words are in competition, they are all candidates to be the target word. As each successive phoneme is identified, words either stay in or drop out of the competition depending on whether they possess the next phoneme. So let’s say that the next phonetic event leads us to identifying the phoneme |t|, giving us |ɑːt| the word ‘are’ drops out of the competition, and when the third occurs |ɑːtɪ| then ‘art’ drops out of the competition. This process continues until all but the target word emerges. This is a gross simplification, but it will give you an idea of the features of models which exist in the activated-candidates-in-competition paradigm. As Magnuson et al (2013) make clear, this is a starting assumption which makes research possible, it is not a research finding.

To be continued.

Magnuson, J. S., Mirman, D., & Myers, E. (2013). Spoken Word Recognition.The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Psychology, 412.